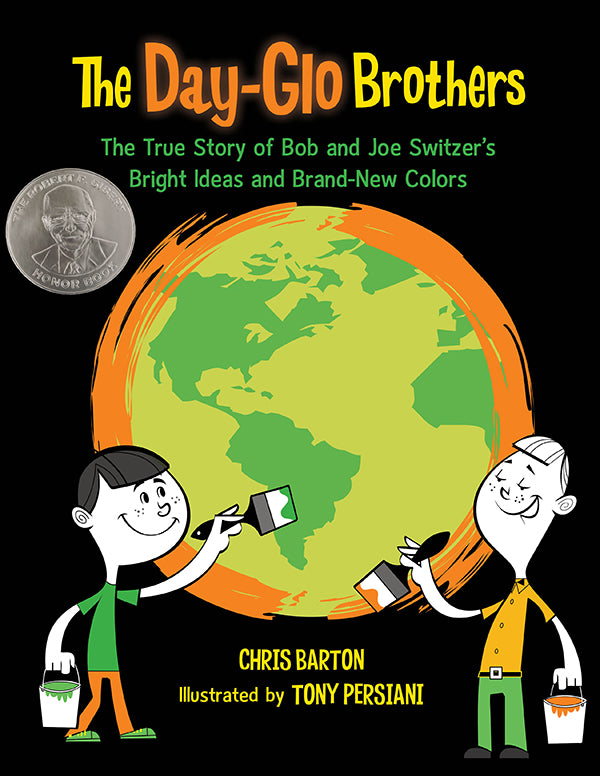

The Day-Glo Brothers

Chris Barton, author

Chris Barton grew up about 80 miles east of Dallas, in the small town of Sulphur Springs, Texas. It was there, at Lamar Elementary, that he wrote the first story that he remembers sharing with the public: The Ozzie Bros. Meet The Monsters, inspired in equal parts by Star Wars (recurring dialogue: "Let's get out of here!"), the Muppets, Abbott and the movie-monster books he loved to check out from the school library.

Read more about Chris.

Tony Persani, illustrator

Tony Persani has created bold and expressive illustrations for newspapers, magazines, television channels, and even sports teams.

Read more about Tony.

A Note from the Author:

I have seen Day-Glo colors my whole life, but I had never considered how those colors came to be until Bob Switzer died in 1997 and I read his obituary in the New York Times. That article introduced me to Bob and Joe Switzer's story.

The story stuck with me, and when I began writing for children a few years later, it was one of the first ones I wanted to tell. But I needed more information about Joe and Bob, and I couldn't find any books about them. Bob's obituary gave the names of his surviving family members—Joe had died in 1973—so I found their phone numbers and began calling.

I received more cooperation from the Switzer family than I could have imagined. Bob's widow, Pat, and Joe's first wife, Elise de Groot, shared their memories with me, as did several of Bob's and Joe's children. I thanked them all. My deepest appreciation goes to Bob and Joe's younger brother, Fred Switzer, who provided a wealth of information and guidance.

Of course, I wish I could have spoken with Joe and Bob themselves. In 1984, shortly before the Switzer family sold the Day-Glo Color Copr., Bob wrote by longhand a seventy-five-page history of their years before moving to Ohio. So I had Bob's version of events, but because Joe died relatively young and had never cared much for writing, his side of the story was harder to come by.

That's why nothing about this project meant more to me than the family's willingness to share Bob's and Joe's original letters, notes, and other materials detailing thier earliest experiments and business successes. I majored in history in college, but I never felt so much like a true historian as when I held those seventy-year-old artifacts in my hands.

—Chris Barton

- Publishers Weekly Best Children's Books

- NY Public Library's Children's Books 2009 - 100 Titles for Reading and Sharing

- Kirkus Reviews' Best Books

- School Library Journal's Best Books

- Robert F. Sibert Honor Book

- ALA Notable Children's Books

- Cybils, Picture Book Nonfiction

- IRA/CBC Children's Choices

- ABC Best Books for Children

- Bank Street College of Education's Best Children's Books of the Year

- PSLA YA Top 40 Non-fiction

- NYSRA Charlotte Award Suggested Reading List, Primary Grades

- Children's Crown Award

Kirkus Reviews, starred review

The Switzer brothers were complete opposites. Older brother Bob was hardworking and practical, while younger brother Joe was carefree and full of creative, wacky ideas. However, when an unexpected injury forced Bob to spend months recovering in a darkened basement, the two brothers happened upon an illuminating adventure—the discovery of Day-Glo colors. These glowing paints were used to send signals in World War II, help airplanes land safely at night and are now found worldwide in art and advertisements (not to mention the entire decade of 1980s fashion). Through extensive research, including Switzer family interviews and Bob's own handwritten account of events, debut author Barton brings two unknown inventors into the brilliant light they deserve. Persiani, in his picture-book debut as well, first limits the palette to grayscale, then gradually increases the use of color as the brothers' experiments progress. The final pages explode in Day-Glo radiance. Rendered in 1950s-cartoon style, with bold lines and stretched perspectives, these two putty-limbed brothers shine even more brightly than the paints and dyes they created.

Publishers Weekly, starred review

In this debut for both collaborators, Barton takes on the dual persona of popular historian and cool science teacher as he chronicles the Switzer brothers' invention of the first fluorescent paint visible in daylight. The aptly named Day-Glo, he explains, started out as a technological novelty act (Joe, an amateur magician, was looking for ways to make his illusions more exciting), but soon became much more: during WWII, one of its many uses was guiding Allied planes to safe landings on aircraft carriers. The story is one of quintessentially American ingenuity, with its beguiling combination of imaginative heroes (“Bob focused on specific goals, while Joe let his freewheeling mind roam every which way when he tried to solve a problem”), formidable obstacles (including, in Bob's case, a traumatic accident), a dash of serendipity and entrepreneurial zeal. Persiani's exuberantly retro 1960s drawings—splashed with Day-Glo, of course—bring to mind the goofy enthusiasm of vintage educational animation and should have readers eagerly following along as the Switzers turn fluorescence into fame and fortune.

School Library Journal, starred review

Before 1935, fluorescent colors did not exist. Barton discusses how two brothers worked together to create the eye-popping hues. Joe Switzer figured out that using a black light to create a fluorescent glow could spruce up his magic act, so the brothers built an ultraviolet lamp. They began to experiment with various chemicals to make glow-in-the-dark paints. Soon Joe used fluorescent-colored paper costumes in his act and word got around. Through trial and error, the brothers perfected their creation. The story is written in clear language and includes whimsical cartoons. While endpapers are Day-Glo bright, most of the story is illustrated in black, white, gray, and touches of color, culminating in vivid spreads. Discussions on regular fluorescence and daylight fluorescence are appended. This unique book does an excellent job of describing an innovative process.

Booklist

Still in their teens in 1933, brothers Bob and Joe Switzer began experimenting with fluorescent colors and trying to create paints that would glow in the dark. Joe saw the potential for improving his magic show, while Bob, who was recovering from an industrial accident, hoped to make some money to pay his medical bills. After years of experimentation, they succeeded in creating paints that glowed in daylight as well as ultraviolet light. The book concludes with explanations of regular and daylight fluorescence as well as a note on the author’s original research for the book. In stylized, digital artwork with a retro feel, Persiani illustrates early scenes of the Switzers’ life in black, white, and shades of gray, then gradually introduces colors. The final double-page spreads are ablaze with Day-Glo yellow, green, and orange. Organizing his material well and writing with a sure sense of what will interest children, Barton creates a picture book that celebrates ingenuity and invention.

The Washington Post

They may be colors you want to wear only during hunting season, but day-glo green, yellow and orange have proved useful, even life-saving, ever since the Switzer brothers figured out fluorescence in the 1930s. First-time author Chris Barton clearly and crisply explains how the two young men managed to work together despite the fact that one wanted to be a magician and the other a physician (before suffering a major head injury). Illustrator Tony Persiani presents a lively cartoonish version of the brothers, starting out in a retro black-and-white world and adding bits of day-glo brightness until the brothers inspect a billboard they created. Not only is the roadside sign flaming orange, but Persiani infuses the whole landscape with fluorescent flavors. Readers will learn the difference between regular and daylight fluorescence, how the Switzers' invention helped win World War II (day-glo buoys, for example, marked mine-free zones) and where fluorescent paint shows up in our daily lives, in everything from golf balls and hula hoops to traffic cones. This engaging picture book makes a bright idea stand out even more.

The New York Times Book Review

If it's narrative you want, you could turn to Chris Barton and Tony Persiani's Day-Glo Brothers: The True Story of Bob and Joe Switzer's Bright Ideas and Brand-New Colors. It's a story in color and about color, in which two sons of a pharmacist, one carefree and into magic, the other studious and into medicine, experimented with fluorescent light in their basement in Berkeley, Calif., in the 1930s and mixed the first Day-Glo paint. It's perfect that they did this in Berkeley, as their colors would play such and interesting role in the postwar West Coast hippie scene. (See Tom Wolfe's first book, "The Kandy-Colored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby," from the toddler era of fun nonfiction.)The brothers, in other words, did the seemingly unimaginable: invented a band of colors new to the world. As with many great inventions, the discovery happened somewhat by accident, while they were making a billboard to grab attention on a nighttime Ohio highway. (They knew their paint was good, just not how good.) In Barton's description of the breakthrough moment, which can stand for all such moments, you can almost hear the echo of Moses and the burning bush: "When the billboard came into view that afternoon, what the brothers saw astonished them. From more than a mile away, it looked like the billboard was on fire!"

The book, which explains the whys and hows of Day-Glo and is illustrated with tremendous Pop Art verve, began with Barton's perusal of The New York Times's obituary page, proving that the dead really do tell the best tales.

Hardcover

ISBN: 978-1-57091-673-1

E-book PDF

ISBN: 978-1-60734-370-7

Ages: 7-10

Page count: 44

8 1/2 x 11